Mike White's latest HBO Max show The White Lotus has arrived and departed, leaving viewers with plenty to chew on surrounding the series' controversial ending. The satirical dramedy drops its audience into the eponymous Hawaiian resort, following several wealthy guests and the havoc they carelessly wreak. Themes of imperialism, classism, and a mercurial moral compass guide these characters through a sun-baked murder mystery of sorts. Critics and fans alike have hailed it as among the most thought-provoking shows in recent memory, and with the anthology series set up for a second season, it's important to understand just how season one tied up its chosen cast and setting.

The White Lotus is, first and foremost, Mike White's creation. He has written screenplays (School of Rock, Nacho Libre), competed in reality television contests (Survivor, The Amazing Race), and co-created his Lotus predecessor Enlightened at HBO with Laura Dern. In an interview with Vulture, White provided insights from his own life that are key to understanding the at-times difficult-to-parse messages in The White Lotus. White wrote and directed every episode of the series, and pieces of his own personal experience reside in several characters. But The White Lotus isn't just Mike White's creation, it also has its finger on the pulse of contemporary American culture in a way few other of its contemporaries can claim.

While Enlightened featured an executive and her escape to a Hawaiian resort (not unlike Connie Britton's Nicole Mossbacher), The White Lotus updates such material with a focus on the hotel staff in addition to its patrons. Such an approach highlights the central themes of wealth and colonialism, challenging how the privileged class can afford to behave carelessly, and the burden this places on marginalized groups and the working class. Though it provides no clear solutions to the dense and complex problems it targets, the show's finale follows its characters to their logical conclusions, as if fated to their ends by mechanisms far beyond the understanding of the rich and the reach of the poor. Some viewers may have been unsatisfied with their favorites' ultimate decisions, but how these ends comment on the show's central themes justifies White's choices.

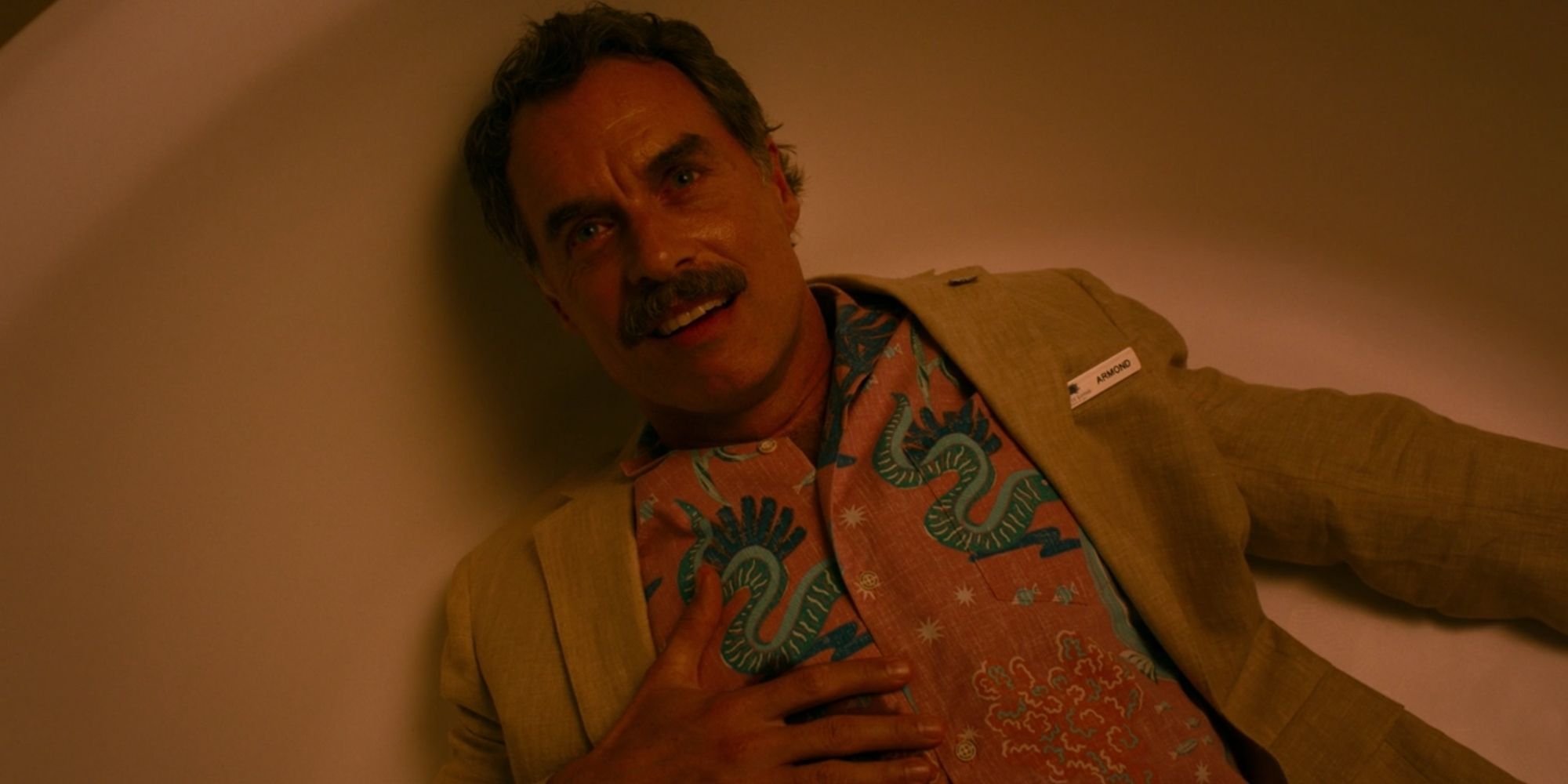

White packs many rich (in more ways than one), well-developed characters into a relatively short runtime. In a brief six episodes, the audience comes to understand the unique wants and needs of each member of the Mossbacher party (daughter Olivia's friend Paula included), the perpetually bewildered heiress Tanya McQuoid (Jennifer Coolidge), the newlyweds Shane (Jake Lacy) and Rachel (Alexandria Daddario), and a slew of hotel workers and other guests overseen by the delightful manager, Armond (Murray Bartlett). As these characters jostle and crash into one another, their relationships move towards inevitable conclusions with an increasingly claustrophobic sense of dread.

In the end, Shane kills his adversary Armond (albeit less intentionally than perhaps expected); Rachel decides to stay the course with her nascent unhappy marriage; the Mossbachers reach an understanding within their own marriage, while their daughter and her friend begin the end of their relationship; Tanya gracelessly bows out of her commitment to spa manager Belinda to chase another guest Greg to Colorado; and, Quinn Mossbacher self-actualizes, dipping the boarding queue to join his newfound Hawaiian friends as they train to row to the big island. It's a lot of ground to cover in one hour of finale, but there's even more lurking beneath the surface.

From the opening moments of The White Lotus, White creates tension with the anonymous "human remains" box and the incessant voiceover "where's your wife?" With this in place, the audience spends the next six episodes wondering which of the colorful cast of characters will end up in that box? And in the finale, they get their answer: Armond. Armond represents the maddening torment of working in hospitality, particularly catering to the vapid whims of the carelessly rich. His fate in the HBO Max series is begun with the double-booking of the Pineapple Suite, but it's sealed with his falling off the wagon.

The pressures and unnecessary stresses of his longtime job push Armond to the edge, and when suddenly presented with Olivia and Paula's stash, he turns to drugs to cope — which leads to his fatally reckless behavior. While Shane getting his comeuppance would have been the satisfying outcome, instead, the opposite occurs. This is important because it supports one of the main themes in The White Lotus: the notion that the working class is powerless against the entrenched mechanisms that unequally distribute wealth. It's a bleak end to a sad story, perhaps, but it's designed this way precisely to highlight the horrors of contemporary western class stratification. And White at least gives Armond some measure of bittersweet fulfillment: he nails dinner and he leaves Shane an odorous parting gift.

In The White Lotus, the character Rachel is no "Lotus-Eater"; she's a writer with journalistic aspirations beyond the listicles she gets assigned. Unfortunately, she's just married one, and he shows his true colors on their honeymoon, becoming a perfect image of the spoiled, hyper-masculine, self-indulgent man-child. Rachel is worn down by him throughout the series: Shane coveting her appearance over character, his incessant complaints and vendetta against the staff, his belittling of her career, and his mother's appearance. When Rachel finally decides to stand up for her principles, she's hardly even acknowledged by Shane — but when she goes searching for advice, she finds Belinda is fresh out of wisdom to dispense. In her, Rachel sees the cost of living under the feet of the wealthy, physically and emotionally spent. Suddenly, sacrificing her principles in exchange for the carelessness wealth would afford seems a good and practical option.

In response to The White Lotus ending criticisms, the creator stated he wanted to create this dynamic from the onset, just as he knew it was Armond he wanted to put in that "human remains" box. White describes Rachel as "a woman who realizes what she’s really married to and what she’s giving up," but that he always knew she'd end up staying with him for three main reasons. First, there's an element of "seduction of a lifestyle," that she's married into wealth and all its advantages, and is therefore naturally incentivized to stay. Second, he imbues Shane with a sense of pathos, insisting that he really does love her, even if he falls short of supporting her when it inconveniences his childlike temperament. This care for the character is essential to his screen presence, especially when White wrote and directed the performance himself. And finally, White cites the difficulty of unraveling her situation as being prohibitive — it'd just be easier to stay the course than back out now, on their honeymoon of all places.

The White Lotus dissects class divide, a scathing satire criticizing the carelessness of wealth. It's a complicated discussion that reflects the creator's own experiences. Mike White has had considerable success in a hearty 20 years as a creative, both critically and commercially, and his diversity of experience informs the characters. He calls Armond the character he relates to the most, often finding himself in the role of being "a 'give the suits what they want' kind of person." But in the same breath, he places himself in Rachel's shoes, often sacrificing his principles to be a writer-for-hire. Finally, his experience as a white man informs his perspectives on Mark and Quinn Mossbacher. In the former, he places his struggles to atone for "the things he can't control." In the latter, he taps into his experience on Survivor and his other world travels, citing a personal desire to escape a world that's "too much with us," and connect with these cultures.

The White Lotus is designed to create conflicted feelings in its audience. Because of White's vantage point on classism and imperialism, the series is designed to provoke debate. Whether it's Nicole Mossbacher's feminism versus Rachel's career aspirations, Olivia and Paula criticizing Mark and Nicole for fetishizing the fruits of imperialism, Paula taking Olivia to task for sticking with her problematic family when push comes to shove, or Quinn choosing personal freedom over wealth in the end, the show functions as a clash of contemporary ideologies. The parable of Belinda and Tanya further illustrates the disparity between the classes, as the former's greatest career opportunity amounts to just another delirious whim in the pseudo-psychotic life of the latter.

The show The White Lotus is a satire and is meant to be read as such. Lani disappears after episode 1 because after she's unable to work, she ceases to exist to the patrons around which the show is centered. Kai is arrested for assault and attempted burglary because to the wealthy, that's just what the help does sometimes — never mind the pillaging of Hawaiian culture and resources by their colonial forefathers. Nicole and Mark repair their marriage — they're perfect for each other, as secure in their status as they are insecure in themselves. Rachel rejoins Shane because the world is a scary place without the privileges (and protections) money affords. Belinda painstakingly puts on her smile again as a group of interchangeable helpers, ready to handle baggage (both material and emotional) prepares for new arrivals at the resort — the endless cycle still churning. And to top it all off, the final shot bears the stain of utilizing marginalized characters for the straight white male to self-actualize — and it's arguably the most gratifying moment in the whole six episodes. Such is the intrinsic cognitive dissonance of The White Lotus.

from ScreenRant - Feed https://ift.tt/2WAvQLg

Skip to main content

Skip to main content

Comments

Post a Comment